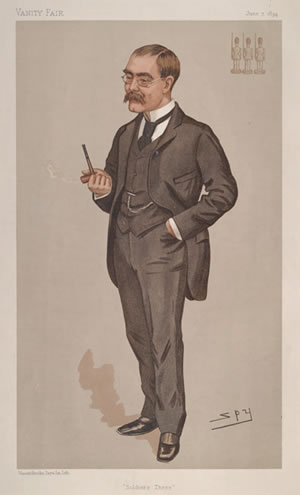

Unquiet

Lands

If the standing

of writers was tradable like stocks, what price would you get for

a Kipling? A scant few pennies? Certainly just a fraction of the value

of, say, a Churchill. Whereas trade in the former has virtually ceased,

Churchills gain in value by the year.

And why should

that be? Both were men of their age (that euphemism suggesting the

maintenance of views unpalatable to modern tastes). Their lives spanned

the pomp of imperialism and witnessed the decline of empire brought

about by the horrors of war. Both railed against this erosion and

both expended energy and time on fruitless attempts to rebuild the

nation’s appetite for influence. Both were militaristic, yet

sentimental about the plight of the “Tommy”. Both were

prone to depression and garrulousness. Both had seen action and were

men of conviction. Both had charm, yet were impatient, irascible and

hard-won. Both were men of the people despite erudition and intellect.

Yet, despite

all this, Churchill remains a popular folk icon while the legacy of

Kipling has hardened and crumbled. A hard man to like, suggested the

obituaries of the time, yet few could be found to own up to their

dislike.

So

much for the man considered to be the people’s poet, a man of

extraordinary literary prowess, born of a journalistic tradition,

whose work was capable of adaptation for musical hall ditties and

Sunday service hymns. Whose tales for children, such as The Jungle

Book, were so whimsical that they have become beloved of Disney cartoons.

Whose grasp of detail and description made him this country’s

first Nobel prize winner for literature and whose finest novel Kim

encapsulates this country’s ambivalent relationship to the subcontinent

in a way that the enlightened products of modern multiculturism have

yet to match.

So

much for the man considered to be the people’s poet, a man of

extraordinary literary prowess, born of a journalistic tradition,

whose work was capable of adaptation for musical hall ditties and

Sunday service hymns. Whose tales for children, such as The Jungle

Book, were so whimsical that they have become beloved of Disney cartoons.

Whose grasp of detail and description made him this country’s

first Nobel prize winner for literature and whose finest novel Kim

encapsulates this country’s ambivalent relationship to the subcontinent

in a way that the enlightened products of modern multiculturism have

yet to match.

Kipling fell

victim to the passing of time and the transient appetites of fashion.

The trade in Kiplings these days is under the counter and conducted

in murky corners, pursued by mucky-handed revisionists who consider

his bombast to be racist and his reputation – from alleged wife-bully

to embittered war monger – to be fair game.

In Today last

month the poet laureate Andrew Motion laid claim to a mission to bring

poetry down from its lofty perch. No figure has done so with greater

effect than Rudyard Kipling who shepherded verse and ballad into the

mainstream and made it say things that people could understand. His

poems filled newspaper columns and his polemics rhymed, scanned, and

were frequently uttered in the dialect of the common man. They offered

an earthy humour as well as an almost mystical hopefulness. They were

as much part of the political landscape as a leader in The Times yet

they educated in form as well as content.

Kipling was a

man of his times. And he has stayed there, stuck like an insect in

amber, only coming alive when his prose and poetry are revivified

in the reading. His most famous poem “If” was recently

voted the nation’s favourite. Yet the poet’s name is mumbled

as an afterthought, almost an embarrassment. As if someone like him

couldn’t possibly write something like that.

As a man obsessed

with privacy, Bateman’s in Burwash was where Kipling constructed

his castle and fortifications, surrounded by lands that he had accumulated

to militate against intrusion.

Every writer

has two lives; the one which he must occupy in order to understand

the society that constructs the backdrop to his tales; and the place

where he goes to retrieve the coloured threads of fiction that he

weaves. Both are so very different and both must be protected one

from the other. Kipling himself alluded to this duality in his autobiography

Something Of Myself when he said: “The magic, you see, lies

in a ring or fence that you take refuge in.”

Outside, the

storm clouds of war might have been gathering but he could not let

those everyday concerns contaminate his complex imagination, the sort

of place where he would discover how elephants grew their trunks,

and where wolves could raise a boy called Mowgli.

Kipling ensured

that the “ring or fence” of Bateman’s was beyond

reach and beyond breach. He moved into the house at the age of 36

in 1902 and was to stay there for the last 34 years of his life. A

wealthy and successful man, his travels had taken him from India,

where he was born in 1865, to South Africa at the time of the Boer

War, and, to North America from where his wife hailed. He drew on

the broadest of canvasses. Yet he chose to settle in a 17th-century

sandstone former ironmaster’s residence with a gloomy interior

of oak panels and small windows which only hinted at the lushness

of the countryside into which it was sunk.

He

was grieving the loss of his daughter Josephine who had died of pneumonia

at six during a journey to America in 1899 at the time of the £9,300

purchase. He would never return to that continent again and, despite

maintaining his extensive travels, he was never as carefree.

He

was grieving the loss of his daughter Josephine who had died of pneumonia

at six during a journey to America in 1899 at the time of the £9,300

purchase. He would never return to that continent again and, despite

maintaining his extensive travels, he was never as carefree.

Bateman’s

suited him and this new sombre outlook. Steeped in history and lost

in the Sussex Weald it was “a real House in which to settle

down for keeps”. Including his help, between 16 and 20 people

lived full time at Bateman’s and, despite his love of privacy,

he was a generous host and would bring down distinguished guests for

dinner parties – journalists, politicians and the giddy gentry.

His life was

managed by the ever-vigilant and often possessive Carrie who nurtured

her own need for obsessive control in the wake of her child’s

death.

Kipling’s

acquisitions didn’t stop with Bateman’s. In 1905 he obtained

the adjoining Dudwell Mill and farm and he removed the waterwheel

and installed a generator. Keen to deter intrusions, he made 14 separate

trades on lands adjoining the estate up to 1928, amassing 300 acres

and absorbing farms and buildings in the vicinity. He stalked the

land and enjoyed the mystical dark underworld of the woodlands, which

inspired magical works such as Puck Of Pook’s Hill and Rewards

And Fairies.

But politics,

inevitably, intervened and fired his thoughts. He turned down honours,

including a knighthood, and other formal recognition, fearing he would

be constrained in what he had to say, particularly about the threat

of conflict in Europe.

When the war

that he had feared and prophesied finally became a reality, he was

active in summoning support for the effort, aiding refugees and devoting

time to the Red Cross. He was immensely proud that his 17-year-old

son secured a commission with the Irish Guards. Although like his

father, son John was shortsighted, Kipling managed to pull some strings

to engineer the commission.

It was therefore

of the greatest tragic irony that John was announced missing in the

Battle of Loos in 1915 on his first day in action. His body was never

found during Kipling’s lifetime and the loss was crippling,

bringing excruciating physical ailments as well as mental anguish.

He joined the

Imperial War Graves Commission as part of his continuing quest to

find his son’s body and, unknown to most, he paid a British

gardener to sound the Last Post at the Menin Gate every night in remembrance

of John.

He was never

to recover, from his personal grief and his horror at the atrocities

of modern warfare. “The embalming of a race,” he said.

His work, dwindling

in output, was shot through with this darkness, with themes of disease,

pain and madness. Two of his three children had died and the third,

Elsie, had married a man of whom her parents disapproved.

On the wider

scene, Kipling began to realise that the “war to end all wars”

was not the last act: he foresaw the rise of Hitler and he maintained

a hatred of Germany, the country which had stolen away his precious

son. With a nation tired of conflict, his urgent message of preparedness

was unpopular. But he was as right about the second world war as he

was about the first although he never lived to see the new horror

commence.

Novelist Hugh

Walpole gave a thumbnail portrait of Kipling’s final years at

Bateman’s: “He’s a zealous propagandist who, having

discovered that the things for which he must propaganda are now all

out of fashion, guards them jealously and lovingly in his heart but

won’t any more trail them about in public. His body is nothing

but his eyes are terrific, lambent, kindly, gentle and exceedingly

proud. Good to us all and we are all shadows to him.”

Rudyard Kipling

died on January 18, 1936, aged 70. It was the 44th anniversary of

his marriage to Carrie and just days before his friend, King George

V died at Sandringham. Kipling’s ashes were laid in Poets’

Corner while the king’s body was lying in state in Westminster

Hall.

“The king

is dead,” said one paper. “And has taken his trumpeter

with him.”

So what of Kipling’s

fortunes today? Aside from the whimsy of his children’s pieces

and his prolific collection of short stories and journalism. What

would he write about in today’s Times say?

Consider this

stanza from his most controversial work, White Man’s Burden.

Take up the

White Man’s burden –

The savage wars of peace –

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Difficult as

it is to read with its barbs and crudeness of language, is that not

the self-same populist, whispered sentiment that emerged when the

G8 met at Gleneagles? The weary West propping up corrupt regimes seemingly

as a matter of eternal moral imperative?

Or this verse

from Tommy.

Yes, makin’

mock o’ uniforms that guard you while you sleep

Is cheaper than them uniforms, an’ they’re starvation

cheap;

An’ hustlin’ drunken soldiers when they’re goin’

large a bit

Is five times better business than paradin’ in full kit.

Then it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy

how’s yer soul?”

But it’s “Thin red line of ’eroes” when the

drums begin to roll,

The drums begin to roll, my boys, the drums begin to roll,

O it’s “Thin red line of ’eroes” when the

drums begin to roll.

Is that not the

sentiment that both summarises and chastises the liberal uncertainty

about reactions to “Our Boys” in Iraq?

Kipling, through

the modern prism, is politically incorrect. But he is influential,

universal and uncompromising. As political correctness itself is fast

becoming a dud currency – and a vile mechanic of self-censorship

– the words of master craftsman Kipling, challenging, robust,

pithy and apposite, may yet find a market.

Investment advice?

Buy a Kipling or two. Their value can go down as well as up, but they

will surely guarantee added interest to any long-term portfolio.

Bateman’s

is maintained by the National Trust just as Kipling left it, displaying

his strong associations with the east with the mill, his study and

his Rolls Royce on display. The house closes in October for the winter

but the extensive gardens, tea-room and shop remain open. Tel: 01435

882302, www.nationaltrust.org.uk